SOD Assay Kit-WST

SOD Assay Kit-WST

To measure the antioxidant capacity (SOD-like activity) of food. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is an antioxidant enzyme that exists in the body and has the function of scavenging superoxide (O₂⁻), which is one of the reactive oxygen species (ROS). This kit can easily measure SOD-like activity using a 96-well microplate.

The test can be performed by simply adding a reagent.

Product information

Antioxidant Capacity Measurement Kit

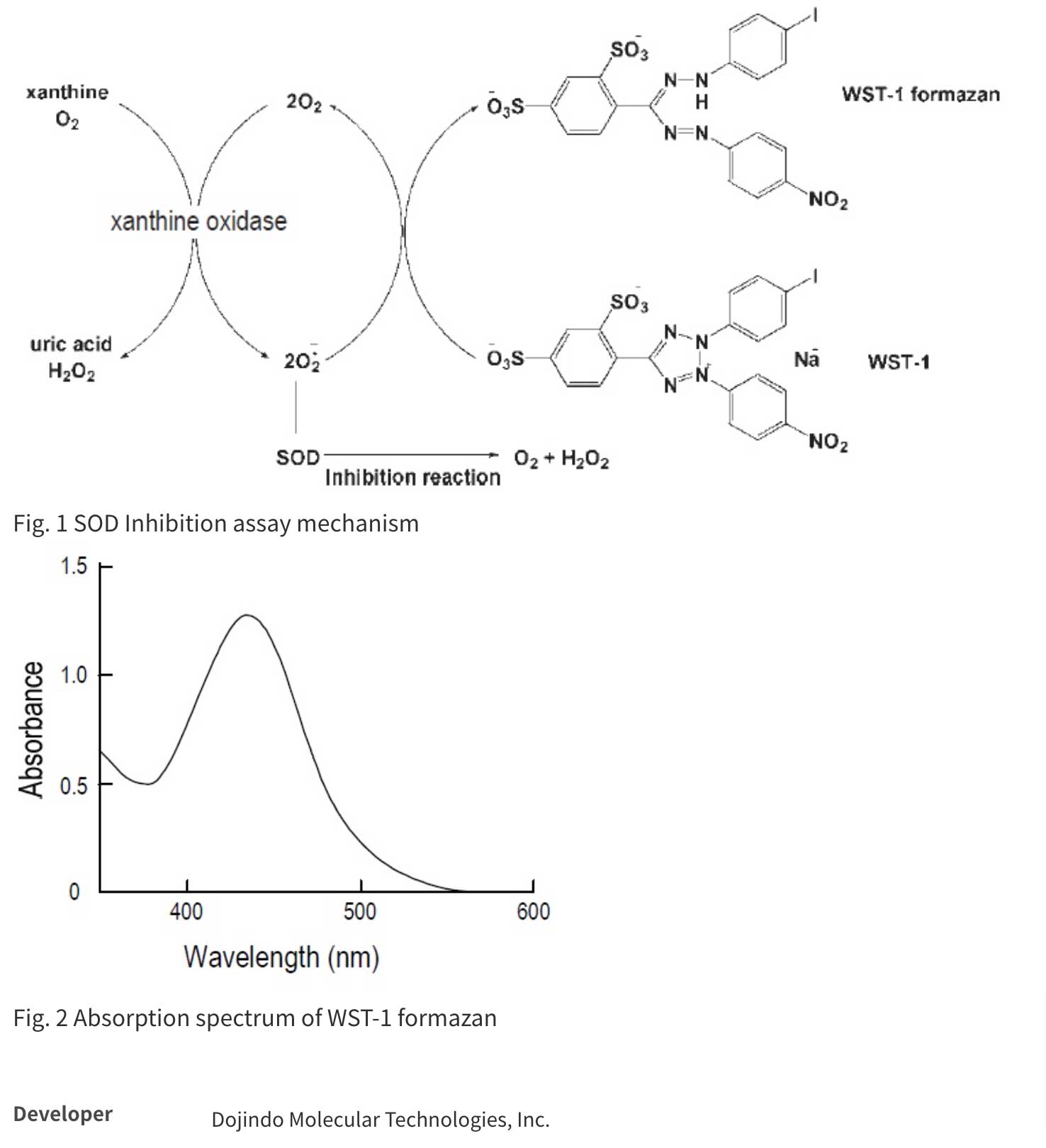

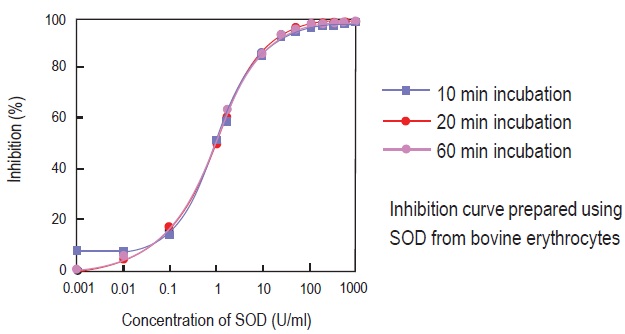

SOD Assay Kit-WST allows a very convenient and highly sensitive SOD assay by utilizing Dojindo’s highly water-soluble tetrazolium salt, WST-1 (2-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfo-phenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, monosodium salt), which produces a water-soluble formazan dye upon reduction with a superoxide anion (Fig. 1). The absorption spectrum is shown in Fig. 2. WST-1 is 70 times less reactive with superoxide anion than cytochrome C; therefore, highly sensitive SOD detection is possible and samples can be diluted with buffer to minimize background problems. WST-1 does not react with the reduced form of xanthine oxidase; therefore, even 100% inhibition with SOD is detectable. The rate of WST-1 reduction by superoxide anion is linearly related to the xanthine oxidase activity and is inhibited by SOD (see figure below). Therefore, the IC50 (50% inhibition concentration) of SOD or SOD-like materials can be determined using colorimetric methods.

Technical info

a)After the addition of enzyme working solution, the mixed solution generates superoxide. Use a multi-channel pipette to add the enzyme working solution to minimize the reaction time lag.

b)If the microplate reader has a temperature control function, incubate the plate on the microplate holder at 37°C.

Preparation of Various Sample Solution

Cells (Adherent cells: 9×106 cells, Leukocytes: 1.2 x107 cells)

1. Harvest cells with a scraper, centrifuge at 2,000 g for 10 min at 4ºC, and discard the supernatant.

2. Wash the cells with 1 ml PBS and centrifuge at 2,000 g for 10 min at 4ºC. Discard the supernatant. Repeat this step.

3. Break cells using the freeze-thaw method (-20ºC for 20 min, then 37ºC bath 10 min, repeat twice).

4. Add 1 ml PBS. If necessary, sonicate the cell lysate on an ice bath (60 W with 0.5 sec interval for 15 min).

5. Centrifuge at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4ºC.

Plant or Vegetable (200 mg)

1. Add 1 ml distilled water, and homogenize the sample using a homogenizer with beads.

2. Filter the homogenate with paper filter, and lyophilize the filtrate.

3. Measure the weight of the lyophilized sample, and dissolve with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) to prepare sample solution.

Tissue (100 mg)

1. Wash the tissue with saline to remove as much blood as possible. Blot the tissue with paper towels and then measure its weight.

2. Add 400-900 μl sucrose buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) and homogenize the sample using Teflon homogenizer. If necessary, sonicate the homogenized sample on an ice bath (60W with 0.5 second intervals for 15 min).

3. Centrifuge the homogenized sample at 10,000 g for 60 min at 4ºC, and transfer the supernatant to a new tube.

Tea (antioxidant activity detection)

1. Add 60 ml boiled water to 10 g of tea, and leave it for 2.5 min.

2. Filter the extract with paper filter and then filter again with a 0.45 μm membrane filter.

3. Dilute the filtrate with distilled water to prepare sample solution.

Erythrocytes or Plasma

1. Centrifuge 2-3 ml of anticoagulant-treated blood (such as heparin 10 U/ml final concentration) at 600 g for 10 min at 4°C.

2. Remove the supernatant and dilute it with saline to use as a plasma sample. Add saline to the pellet to prepare the same volume, and suspend the pellet.

3. Centrifuge the pellet suspension at 600 g for 10 min at 4ºC, and discard the supernatant.

4. Add the same volume of saline, and repeat Step 3 twice.

5. Suspend the pellet with 4 ml distilled water, then add 1 ml ethanol and 0.6 ml chloroform.

6. Shake the mixture vigorously with a shaker for 15 min at 4°C.

7. Centrifuge the mixture at 600 g for 10 min at 4ºC and transfer the upper water-ethanol phase to a new tube.

8. Mix 0.1 ml of the upper phase with 0.7 ml distilled water, and dilute with 0.25% ethanol to prepare sample solution.

Extracellular SOD (EC-SOD)

1. Prepare a 0.5 ml volume of Con A-sepharose column equilibrated with PBS.

2. Apply supernatant of a tissue homogenate on the column, and leave the column for 5 min at room temperature.

3. Add total 10 ml PBS to wash the column.

4. Add 1 ml of 0.5 M α-methylmannoside/PBS, and collect the eluate. Repeat 5 times.

5. Use the eluate for the SOD assay without dilution. If the SOD activity is high enough, dilute the eluate with PBS.

Wine (antioxidant activity detection)

1. Filter wine with a 0.45 μm membrane filter.

2. Dilute the filtrate with distilled water to prepare sample solution.

Data

Inhibition curve by WST Method

Fig. 5 Inhibition curve prepared by different data acquisition times

References

2) H. Ukeda, D. Kawana, S. Maeda and M. Sawamura, "Spectrophotometric Assay for Superoxide Dismutase Based on the Reduction of Highly Water-soluble Tetrazolium Salts by Xanthine-Xanthine Oxidase", Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem., 1999, 63, 485.

3) H. Ukeda, T. Shimamura, M. Tsubouchi,Y. Harada, Y. Nakai and M. Sawamura, "Spectrophotometric Assay of Superoxide Anion Formed in Maillard Reaction Based on Highly Water-soluble Tetrazolium Salt", Anal. Sci., 2002, 18, 1151.

4) N. Tsuji, N. Hirayanagi, M. Okada, H. Miyasaka, K. Hirata, M. H. Zenk and K. Miyamoto, "Enhancement of Tolerance to Heavy Metals and Oxidative Stress in Dunaliella Tertiolecta by Zn-induced Phytochelatin Synthesis", Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 2002, 293, 653.

5) A. Sakudo, D. C. Lee, K. Saeki, Y. Nakamura, K. Inoue, Y. Matsumoto, S. Itohara and T. Onodera, "Impairment of Superoxide Dismutase Activation by N-Terminally Truncated Prion Protein (PrP) in PrP-deficient Neuronal Cell Line", Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 2003, 308, 660.

6) J.-H. Zhu, X. Zhang, J. P. Mcclung and X. G. Lei, "Impact of Cu,Zn-Superoxide Dismutase and Se-Dependent Glutathione Peroxidase-1 Knockouts on Acetaminophen-Induced Cell Death and Related Signaling in Murine Liver", Exp. Biol. Med., 2006, 231, 1726.

7) H. R. Rezvani, S. Dedieu, S. North, F. Belloc, R. Rossignol, T. Letellier, H. de Verneuil1, A. Taieb1, F.Mazurier, "HIF-1α: a Key Ffactor in the Keratinocyte Response to UVB Exposure", J. Biol. Chem., 2007, 10, 1074.

8) S. Goldstein and G. Czapski, "Comparison Between Different Assays for Superoxide Dismutase-like Activity", Free Rad. Res. Comms., 1991, 12, 5.

9) R. H. Burdon, V. Gill and C. Rice-Evans, "Reduction of a Tetrazolium Salt and Superoxide Generation in Human Tumor Cells (HeLa)", Free Rad. Res. Commun., 1993,18, 369.

10) Y. Sakurai, I. Anzai and Y. Furukawa, "A Primary Role for Disulfide Formation in the Productive Folding of Prokaryotic Cu,Zn-superoxide Dismutase", J. Biol. Chem., 2014, 289(29), 20139.

11) A. Weichert, A. S. Besemer, M. Liebl, N. Hellmann, I. Koziollek-Drechsler, P. Ip, H. Decker, J. Robertson, A. Chakrabartty, C. Behl and A. M. Clement, "Wild-type Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase stabilizes mutant variants by heterodimerization", Neurobiol. Dis., 2014, 62, 479.

12) J. M. Hartney, T. Stidham, D. A. Goldstrohm, R. E. Oberley-Deegan, M. R. Weaver, Z. Valnickova-Hansen, C. Scavenius, R. K.P. Benninger, K. F. Leahy, R. Johnson, F. Gally, B. Kosmider, A. K. Zimmermann, J. J. Enghild, E. Nozik-Grayck and R. P. Bowler, "A common polymorphism in extracellular superoxide dismutase affects cardiopulmonary disease risk by altering protein distribution", Circ Cardiovasc Genet, 2014, 7(5), 659.

13) J. Wu, Y. Sun, Y. Zhao, J. Zhang, L. Luo, M. Li, J. Wang, H. Yu, G. Liu, L. Yang, G. Xiong, J. Zhou, J. Zuo, Y. Wang and J. Li, "Deficient plastidic fatty acid synthesis triggers cell death by modulating mitochondrial reactive oxygen species", Cell Res., 2015, 25(5), 621.

14) E. Harunari, C. Imada, Y. Igarashi, "Konamycins A and B and Rubromycins CA1 and CA2, Aromatic Polyketides from the Tunicate-Derived Streptomyces hyaluromycini MB-PO13T'", J. Nat. Prod., 2019, 82, (6), 1609-1615.

15) N. Kajihara, D. Kukidome, K. Sada, H. Motoshima, N. Furukawa, T. Matsumura, T. Nishikawa and E. Araki, "Low glucose induces mitochondrial reactive oxygen species via fatty acid oxidation in bovine aortic endothelial cells", J Diabetes Investig, 2017, 8, (6), 750.

16) H- J. Kim, H- J. Kim, J. Jeon, K- C. Nam, K- S. Shim, J- H. Jung, K. S. Kim, Y. Choi, S- H. Kim, A. Jang, Comparison of the quality characteristics of chicken breast meat from conventional and animal welfare farms under refrigerated storage', Poultry Science., 2020, 99, 1788-1796.

17) T. Shoji, S. Masumoto, N. Moriichi, Y. Ohtake, T. Kanda, Administration of Apple Polyphenol Supplements for Skin Conditions in Healthy Women: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial', Nutrients., 2020, 12, (1071), .

18) Y. Hirata, Y. Ito, M. Takashima, K Yagy, K. Oh-Hashi, H. Suzuki, K. Ono, K. Furuta and M. Sawada, Novel Oxindole-Curcumin Hybrid Compound for Antioxidative Stress and Neuroprotection.', ACS Chem. Neurosci.., 2020, 11, (1), 76-85.

Recent Publications

Samples from: hESCs

Treatments: SOD-1 overexpressing

References: Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Model Derived from Human Embryonic Stem Cells Overexpressing Mutant Superoxide Dismutase 1

T. Wada, et al., Stem Cells Trans Med, 1, 396(2012)

Samples from: mouse heart, liver

Treatments: tetrathiomolybdate

References: Copper chelation by tetrathiomolybdate inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in vivo

H. Wei, et al., Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 301, H712(2011)

Samples from: MEF cells

Treatments: presenilin knock-out

References: Presenilins Promote the Cellular Uptake of Copper and Zinc and Maintain Copper Chaperone of SOD1-dependent Copper/Zinc Superoxide Dismutase Activity

M. A. Greenough, et al., J Biol Chem, 286, 9776(2011)

Samples from: mouse lung

Treatments: SOD3 knockout, overexpressing

References: Extracellular superoxide dismutase protects against pulmonary emphysema by attenuating oxidative fragmentation of ECM

H. Yao, et al., PNAS, 107, 15571(2010)

Samples from: mouse liver Nrf2

Treatments: nuclear factor-E2-related factor-2

References: Deletion of nuclear factor-E2-related factor-2 leads to rapid onset and progression of nutritional steatohepatitis in mice

H. Sugimoto, et al., Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 298, G283(2010)

Samples from: bacteria (Francisella strains)

Treatments: gallium-transferrin

References: Gallium Disrupts Iron Uptake by Intracellular and Extracellular Francisella Strains and Exhibits Therapeutic Efficacy in a Murine Pulmonary Infection Model

O. Olakanmi, et al., Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 54, 244(2010)